How the Juggernaut of an industry becomes bankrupt

Kodak, as we know it today, was founded in the year 1888 by George Eastman as ‘The Eastman Kodak Company’. It was the most famous name in the world of photography and videography in the 20th century. Kodak brought about a revolution in the photography and videography industries.

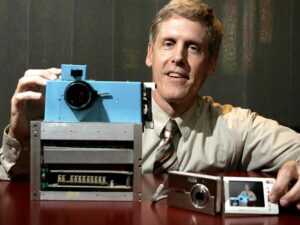

At the time when only huge companies could access the cameras used for recording movies, Kodak enabled the availability of cameras to every household by producing equipment that was portable and affordable. Kodak was the most dominant company in its field for almost the entire 20th century, yet there are few corporate blunders as staggering as Kodak’s missed opportunities in digital photography, a technology that it invented.

This strategic failure was the direct cause of Kodak’s decades-long decline as digital photography destroyed its film-based business model. But to understand why, first we must understand the company’s business model.

Kodak adopted the ‘razor and blades’ business plan. The idea behind this plan is to first sell the razors (the cameras in this case) with a small margin of profit. After buying the razor, the customers will have to purchase the consumables (such as films, printing sheets, and other accessories) again and again; hence, sell the blades at a high-profit margin. Using this business model, Kodak was able to generate massive revenues and turned into a money-making machine.

As technology progressed, the use of films and printing sheets gradually came to a halt. This was due to Steve Sasson, the Kodak engineer who invented the first digital camera in 1975 and characterized initial corporate response as “That’s cute, but don’t tell anyone about it. That’s how you shoot yourself in the foot!”

To demonstrate the extent of Kodak’s denial of the truth, let’s take a look at one story that Vince Barabba recounts from 1981, when he was Kodak’s head of market intelligence. Around the time that Sony introduced the first electronic camera, one of Kodak’s largest retailer photo finishers asked him whether they should be concerned about digital photography. With the support of Kodak’s CEO, Barabba conducted a very extensive research effort that looked at the core technologies and likely adoption curves around silver halide film versus digital photography. The study’s projections were based on numerous factors, including: the cost of digital photography equipment; the quality of images and prints; and the interoperability of various components, such as cameras, displays, and printers.

The results of the study produced both “bad” and “good” news. The “bad” news was that digital photography had the potential capability to replace Kodak’s established film based business. The “good” news was that it would take some time for that to occur and that Kodak had roughly ten years to prepare for the transition. History proved the study’s conclusions to be remarkably accurate, both in the short and long term.

The problem is that, during its 10-year window of opportunity, Kodak did little to prepare for the later disruption. In fact, Kodak made exactly the mistake that George Eastman, its founder, avoided twice before, when he gave up a profitable dry-plate business to move to film and when he invested in color film even though it was demonstrably inferior to black and white film (which Kodak dominated).

After the digital camera became popular, Kodak spent almost 10 years arguing with Fuji Films, its biggest competitor, that the process of viewing an image captured by the digital camera was a typical process and people loved the touch and feel of a printed image. Kodak believed that the citizens of the United States of America would always choose it over Fuji Films, a foreign company.

To see the video of the podcast click here

Fuji Films and many other companies focused on gaining a foothold in the photography & videography segment rather than engaging in a verbal spat with Kodak. And once again, Kodak wasted time promoting the use of film cameras instead of emulating its competitors. It completely ignored the feedback from the media and the market. Kodak tried to convince people that film cameras were better than digital cameras and lost 10 valuable years in the process.

Kodak management not only presided over the creation technological breakthroughs but was also presented with an accurate market assessment about the risks and opportunities of such capabilities. Yet Kodak failed in making the right strategic choices.

Kodak failed to realize that its strategy which was effective at one point was now depriving it of success. Rapidly changing technology and market needs negated the strategy. When Kodak finally understood and started the sales and the production of digital cameras, it was too late. Many big companies had already established themselves in the market by then and Kodak couldn’t keep pace with the big shots.

Post Comment